- Home

- Editorial

- News

- Practice Guidelines

- Anesthesiology Guidelines

- Cancer Guidelines

- Cardiac Sciences Guidelines

- Critical Care Guidelines

- Dentistry Guidelines

- Dermatology Guidelines

- Diabetes and Endo Guidelines

- Diagnostics Guidelines

- ENT Guidelines

- Featured Practice Guidelines

- Gastroenterology Guidelines

- Geriatrics Guidelines

- Medicine Guidelines

- Nephrology Guidelines

- Neurosciences Guidelines

- Obs and Gynae Guidelines

- Ophthalmology Guidelines

- Orthopaedics Guidelines

- Paediatrics Guidelines

- Psychiatry Guidelines

- Pulmonology Guidelines

- Radiology Guidelines

- Surgery Guidelines

- Urology Guidelines

GOI Standard Treatment Guidelines for Neonatal Seizures

Ministry of Health and Family Welfare , Government of India (GOI) has released Standard Treatment Guidelines for Neonatal Seizures which have been prepared by Dr. Ramesh Agarwal Assistant Professor Neonatology at All India Institute of Medical Science.

Neonatal seizures (NS) are the most frequent and distinctive clinical manifestation of neurological dysfunction in the newborn infant. Infants with NS are at high risk of neonatal death or neurological impairment and epilepsy disorders in later life.

Following are the major recommendations :

b) Case definition and classification:

A seizure is defined clinically as a paroxysmal alteration in neurologic function, i.e. motor, behavior and/or autonomic function.

Four types of NS have been identified- subtle, clonic, tonic and myoclonic. Myoclonic seizures carry the worst prognosis in terms of neurodevelopmental outcome and seizure recurrence. Focal clonic seizures have the best prognosis.

| In secondary level hospital | At tertiary care centers |

| A clinical definition should be used for recognition and classification of NS | The diagnosis essentially is clinical. However sophisticated investigations such as EEG may be employed for confirmation and further classification. |

b) INCIDENCE OF THE CONDITION IN OUR COUNTRY

The incidence of NS is 2.8 per 1000 in infants with birth weights of more than 2500 g; it is higher in preterm low birth weight neonates – as high as 57.5 per 1000 in very low birth weight infants.

c) DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The most common causes of seizures as per the recently published studies from the country are hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy, metabolic disturbances (hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia), and meningitis.

a) PREVENTION AND COUNSELING

Good obstetric and neonatal care would go a long way in prevention of neonatal seizures. Screening and management of polycythemia and hypoglycemia can prevent seizure occurrence due to these reasons. Avoiding animal milk feeding by exclusive breastfeeding may reduce seizures due to llate-onset hypocalcemia.

b) OPTIMAL DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA, INVESTIGATIONS, TREATMENT & REFERRAL CRITERIA

Approach and diagnosis

| In secondary level hospital | At tertiary care centers |

| · Clinical evaluation · Measurement of blood glucose, calcium, hematocrit · Lumbar puncture | · Clinical evaluation · Measurement of blood glucose, calcium, hematocrit · Lumbar puncture · Neuroimaging (USG brian for preterm; CT/MRI for term baby · EEG |

Detailed approach to an infant with neonatal seizures

1. History

Seizure history: A complete description of the seizure should be obtained from the parents/attendant. History of associated eye movements, restraint of episode by passive flexion of the affected limb, change in color of skin (mottling or cyanosis), autonomic phenomena, and whether the infant was conscious or sleeping at the time of seizure should be elicited.

Antenatal history: History suggestive of intrauterine infection, maternal diabetes, and narcotic addiction should be elicited in the antenatal history. A history of sudden increase in fetal movements may be suggestive of intrauterine convulsions.

Perinatal history: Perinatal asphyxia is the commonest cause of neonatal seizures and a detailed history including history of fetal distress, decreased fetal movements, instrumental delivery, need for resuscitation in the labor room, Apgar scores, and abnormal cord pH (<7) and base deficit (>10 mEq/L) should be obtained.

Family history: History of consanguinity in parents, family history of seizures or mental retardation and early fetal/neonatal deaths would be suggestive of inborn errors of metabolism. History of seizures in either parent or sib(s) in the neonatal period may suggest benign familial neonatal convulsions (BFNC).

2. Examination

Vital signs: Heart rate, respiration, blood pressure, capillary refill time and temperature should be recorded in all infants.

General examination: Gestation, birth-weight, and weight for age should be recorded as they may provide important clues to the etiology – for example, seizures in a term 'well baby' may be due to subarachnoid hemorrhage while seizures in a large for date baby may be secondary to hypoglycemia.

CNS examination: Presence of a bulging anterior fontanel may be suggestive of meningitis or intracranial hemorrhage. A detailed neurological examination should include assessment of consciousness (alert/drowsy/comatose), tone (hypotonia or hypertonia), and fundus examination for chorioretinitis.

Systemic examination: Presence of hepatosplenomegaly or an abnormal urine odor may be suggestive of IEM. The skin should be examined for the presence of any neurocutaneous markers. Presence of hypopigmented macules or ash-leaf spot would be suggestive of tuberous sclerosis.

3. Investigations

| In secondary level hospitals | At tertiary care centers |

| · blood sugar measurement · sepsis work up and LP · rule out polycythemia | · blood sugar, calcium and electrolyte measurement · sepsis work up and LP · rule out polycythemia · neuroimaging · metabolic work up · EEG |

Essential investigations: Investigations that should be considered in all neonates with seizures include blood sugar, serum electrolytes (Na, Ca, Mg), cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) examination, cranial ultrasound (US), and electroencephalography (EEG). CSF examination should be done in all cases as seizures may be the first sign of meningitis. CSF study may be withheld temporarily if severe cardiorespiratory compromise is present or even omitted in infants with severe birth asphyxia (documented abnormal cord pH/base excess and onset within 12-24 hrs). An arterial blood gas (ABG) may have to be performed if IEM is strongly suspected.

Imaging: Neurosonography is an excellent tool for detection of intraventricular and parenchymal hemorrhage but is unable to detect SAH and subdural hemorrhage. It should be done in all infants with seizures. CT scan should be done in all infants where an etiology is not available after the first line of investigations. It can be diagnostic in subarachnoid hemorrhage and developmental malformations. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is indicated only if investigations do not reveal any etiology and seizures are resistant to usual anti-epileptic therapy.

Electroencephalogram (EEG): EEG has both diagnostic and prognostic role in seizures. It should be done in all neonates who need anticonvulsant therapy. Ictal EEG may be useful for the diagnosis of suspected seizures and also for diagnosis of seizures in muscle-relaxed infants.

Management

| In secondary level hospitals | At tertiary care centers |

| · Stabilize the baby · Correct hypoglycemia or hypocalcemia, if present · Anti-epileptic drug therapy (AED): phenobarbitone is the first choice · Refer if intractable seizures, or baby requires ventilation | · Stabilize the baby · Correct hypoglycemia or hypocalcemia, if present · Anti-epileptic drug therapy (AED): phenobarbitone is the first choice Use additional drugs to control seizures · Management of concurrent illnesses |

Detailed approach to an infant with neonatal seizures

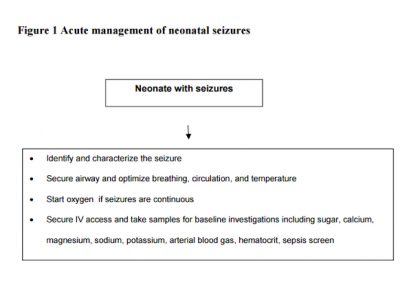

1. Initial medical management:

The first step in successful management of seizures is to nurse the baby in thermoneutral environment and to ensure airway, breathing, and circulation (TABC). Oxygen should be started, IV access should be secured, and blood should be collected for glucose and other investigations. A brief relevant history should be obtained and quick clinical examination should be performed. All this should not require more than 2-5 minutes.

2. Correction of hypoglycemia and hypocalcemia:

If glucostix shows hypoglycemia or if there is no facility to test blood sugar immediately, 2 ml/kg of 10% dextrose should be given as a bolus injection followed by a continuous infusion of 6-8 mg/kg/min.

If hypoglycemia has been treated or excluded as a cause of convulsions, the neonate should receive 2 ml/kg of 10% calcium gluconate IV over 10 minutes under strict cardiac monitoring. If ionized calcium levels are suggestive of hypocalcemia, the newborn should receive calcium gluconate at 8 ml/kg/d for 3 days. If seizures continue despite correction of hypocalcemia, 0.25 ml/kg of 50% magnesium sulfate should be given intramuscularly (IM).

3. Anti-epileptic drug therapy (AED)

Anti-epileptic drugs (AED) should be considered in the presence of even a single clinical seizure since clinical observations tend to grossly underestimate electrical seizures (diagnosed by EEG) and facilities for continuous EEG monitoring are not universally available. If aEEG is being used, eliminating all electrical seizure activity should be the goal of AED therapy. AED should be given if seizures persist even after correction of hypoglycemia/ hypocalcemia.

Phenobarbitone (Pb)

It is the drug of choice in neonatal seizures. The dose is 20 mg/kg/IV slowly over 20 minutes (not faster than 1 mg/kg/min). If seizures persist after completion of this loading dose, additional doses of phenobarbitone 10 mg/kg may be used every 20-30 minutes until a total dose of 40 mg/kg has been given. The maintenance dose of Pb is 3-5 mg/kg/day in 1-2 divided doses, started 12 hours after the loading dose.

Phenytoin

Phenytoin is indicated if the maximal dose of phenobarbitone (40 mg/kg) fails to resolve seizures or earlier, if adverse effects like respiratory depression, hypotension or bradycardia ensue with phenobarbitone. The dose is 20 mg/kg IV at a rate of not more than 1 mg/kg/min under cardiac monitoring. Phenytoin should be diluted in normal saline as it is incompatible with dextrose solution. A repeat dose of 10 mg/kg may be tried in refractory seizures. The maintenance dose is 3-5 mg/kg/d (maximum of 8 mg/kg/d) in 2-4 divided doses. Oral suspension has very erratic absorption from gut in neonates, so it should be avoided. Thus only IV route is preferred in neonates and it should preferably be discontinued before discharge.

Benzodiazepines

This group of drugs may be required in up to 15-20% of neonatal seizures. The commonly used benzodiazepines are lorazepam and midazolam. Diazepam is generally avoided in neonates due to its short duration of action, narrow therapeutic index, and because of the presence of sodium benzoate as a preservative. Lorazepam is preferred over diazepam as it has a longer duration of action and results in less adverse effects (sedation and cardiovascular effects). Midazolam is faster acting than lorazepam and may be administered as an infusion. It causes less respiratory depression and sedation than lorazepam. However, when used as continuous infusion, the infant has to be monitored for respiratory depression, apnea, and bradycardia (equipment for resuscitation and assisted ventilation should be available at the bedside of all neonates given multiple doses of AED).

The doses of these drugs are given below:

Lorazepam: 0.05 mg/kg IV bolus over 2-5 minutes; may be repeated Midazolam: 0.15 mg/kg IV bolus followed by infusion of 0.1 to 0.4 mg/kg/hour. According to Volpe, the expected response of neonatal clinical seizures to anticonvulsants is 40% to the initial 20-mg/kg loading dose of phenobarbitone, 70% to a total of 40 mg/kg of Pb, 85% to a 20-mg/kg of phenytoin, and 95% to 100% to 0.05 to 0.1 mg/kg lorazepam.1

Maintenance anti-epileptic therapy

Principles of AED used in older children and adults are applicable to neonates also. Monotherapy is the most appropriate strategy to control seizures. Attempts should be made to stop all anti-epileptic drugs and wean the baby to only phenobarbitone at 3-5 mg/kg/day. If seizures are uncontrolled or if clinical toxicity appears, a second AED may be added. The choice may vary from phenytoin, carbamezepine, and valproic acid.

When to discontinue AED

This is highly individualized and no specific guidelines are available. We follow an adaptation of the protocol recommended by Volpe. We usually try to discontinue all medication at discharge if clinical examination is normal, irrespective of etiology and EEG. If a neurological examination is persistently abnormal at discharge, AED is continued and the baby is reassessed at one month. If the baby is normal on examination and seizure free at 1 month, phenobarbitone is discontinued over 2 weeks. If a neurological assessment is not normal, an EEG is obtained. If EEG is not overtly paroxysmal, phenobarbitone is tapered and stopped. If EEG is overtly abnormal, the infant is reassessed in the same manner at 3 months and then 3 monthly to 1 year of age. The goal is to discontinue phenobarbitone as early as possible.

Disclaimer: This site is primarily intended for healthcare professionals. Any content/information on this website does not replace the advice of medical and/or health professionals and should not be construed as medical/diagnostic advice/endorsement or prescription. Use of this site is subject to our terms of use, privacy policy, advertisement policy. © 2020 Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt Ltd