- Home

- Editorial

- News

- Practice Guidelines

- Anesthesiology Guidelines

- Cancer Guidelines

- Cardiac Sciences Guidelines

- Critical Care Guidelines

- Dentistry Guidelines

- Dermatology Guidelines

- Diabetes and Endo Guidelines

- Diagnostics Guidelines

- ENT Guidelines

- Featured Practice Guidelines

- Gastroenterology Guidelines

- Geriatrics Guidelines

- Medicine Guidelines

- Nephrology Guidelines

- Neurosciences Guidelines

- Obs and Gynae Guidelines

- Ophthalmology Guidelines

- Orthopaedics Guidelines

- Paediatrics Guidelines

- Psychiatry Guidelines

- Pulmonology Guidelines

- Radiology Guidelines

- Surgery Guidelines

- Urology Guidelines

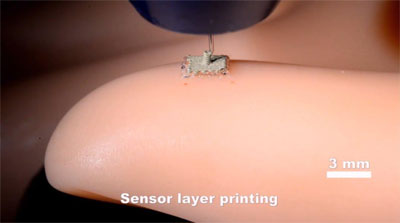

Robotic Surgery Breakthrough : 3D-printed bionic skin could give robots the sense of touch

Engineering researchers at the University of Minnesota have developed a revolutionary process for 3D printing stretchable electronic sensory devices that could give robots the ability to feel their environment. The discovery is also a major step forward in printing electronics on real human skin.

"This stretchable electronic fabric we developed has many practical uses," said Michael McAlpine, a University of Minnesota mechanical engineering associate professor and lead researcher on the study. "Putting this type of 'bionic skin' on surgical robots would give surgeons the ability to actually feel during minimally invasive surgeries, which would make surgery easier instead of just using cameras like they do now. These sensors could also make it easier for other robots to walk and interact with their environment."

McAlpine, who gained international acclaim in 2013 for integrating electronics and novel 3D-printed nanomaterials to create a "bionic ear," says this new discovery could also be used to print electronics on real human skin. This ultimate wearable technology could eventually be used for health monitoring or by soldiers in the field to detect dangerous chemicals or explosives.

"While we haven't printed on human skin yet, we were able to print on the curved surface of a model hand using our technique," McAlpine said. "We also interfaced a printed device with the skin and were surprised that the device was so sensitive that it could detect your pulse in real time."

McAlpine and his team made the unique sensing fabric with a one-of-a kind 3D printer they built in the lab. The multifunctional printer has four nozzles to print the various specialized "inks" that make up the layers of the device -- a base layer of silicone, top and bottom electrodes made of a conducting ink, a coil-shaped pressure sensor, and a sacrificial layer that holds the top layer in place while it sets. The supporting sacrificial layer is later washed away in the final manufacturing process.

Surprisingly, all of the layers of "inks" used in the flexible sensors can set at room temperature. Conventional 3D printing using liquid plastic is too hot and too rigid to use on the skin. These flexible 3D printed sensors can stretch up to three times their original size.

"This is a completely new way to approach 3D printing of electronics," McAlpine said. "We have a multifunctional printer that can print several layers to make these flexible sensory devices. This could take us into so many directions from health monitoring to energy harvesting to chemical sensing."

Researchers say the best part of the discovery is that the manufacturing is built into the process.

"With most research, you discover something and then it needs to be scaled up. Sometimes it could be years before it ready for use," McAlpine said. "This time, the manufacturing is built right into the process so it is ready to go now."

The researchers say the next step is to move toward semiconductor inks and printing on a real body.

"The possibilities for the future are endless," McAlpine said.

In addition to McAlpine, the research team includes University of Minnesota Department of Mechanical Engineering graduate students Shuang-Zhuang Guo, Kaiyan Qiu, Fanben Meng, and Sung Hyun Park.

The research was funded by the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health (Award No. 1DP2EB020537). The researchers used facilities at the University of Minnesota Characterization Facility and Polymer Characterization Facility for testing.

Disclaimer: This site is primarily intended for healthcare professionals. Any content/information on this website does not replace the advice of medical and/or health professionals and should not be construed as medical/diagnostic advice/endorsement or prescription. Use of this site is subject to our terms of use, privacy policy, advertisement policy. © 2020 Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt Ltd