- Home

- Editorial

- News

- Practice Guidelines

- Anesthesiology Guidelines

- Cancer Guidelines

- Cardiac Sciences Guidelines

- Critical Care Guidelines

- Dentistry Guidelines

- Dermatology Guidelines

- Diabetes and Endo Guidelines

- Diagnostics Guidelines

- ENT Guidelines

- Featured Practice Guidelines

- Gastroenterology Guidelines

- Geriatrics Guidelines

- Medicine Guidelines

- Nephrology Guidelines

- Neurosciences Guidelines

- Obs and Gynae Guidelines

- Ophthalmology Guidelines

- Orthopaedics Guidelines

- Paediatrics Guidelines

- Psychiatry Guidelines

- Pulmonology Guidelines

- Radiology Guidelines

- Surgery Guidelines

- Urology Guidelines

Pseudo-Wellens syndrome associated with acute pancreatitis: a case report

Dr V. S. Effoe at Atlanta Veterans Health Care System, Decatur, GA, USA and colleagues have reported a rare case of Pseudo-Wellens syndrome associated with acute pancreatitis. The case has appeared in the Journal of Medical Case Reports.

Chest pain associated with transient electrocardiogram changes mimicking an acute myocardial infarction has been described in acute pancreatitis. These ischemic electrocardiogram changes can present a diagnostic dilemma, especially when patients present with concurrent angina pectoris and epigastric pain warranting noninvasive or invasive imaging studies.ECG changes like characteristic biphasic or symmetrical T-wave inversion with normal precordial R-wave progression and the absence of Q waves in the right precordial leads associated with causes other than LAD stenosis have been described as pseudo-Wellens' syndrome.

A 45-year-old African-American man presented to the emergency department (ED) with over 36 hours of epigastric pain and left-sided chest pain. The patient described his chest pain as a pressure-like sensation, rated 9/10, radiating to his left arm and associated with nausea and dyspnea, but no vomiting or diaphoresis. He denied palpitations, presyncopal symptoms, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, or lower leg swelling. His pain had worsened over the 24 hours preceding his ED visit. His past medical history was significant for alcohol and tobacco use disorders. He had no personal history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, or diabetes. He was taking no medications at home, and he had no drug allergies. His mother had diabetes, but he had no family history of early coronary heart disease. He lived with his wife and adult children. Of note, the patient was a current drinker consuming at least 1 pint of liquor daily and a current smoker with a 20-pack-year history. He had been treated for gastritis at another health facility in the past year, where he had presented with abdominal pain.

On physical examination in the ED, the patient was in mild distress. His blood pressure (BP) was 156/101 mmHg; his pulse was 75 beats per minute; his respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute; his temperature 36.8 °C; and his body mass index 25.5 kg/m2. He appeared anxious and had epigastric tenderness, but he did not have jugular venous distention, carotid bruits, or cardiac murmurs. The rest of his physical examination was unremarkable. Table 1 displays his laboratory test results upon presentation and 12 hours afterwards.

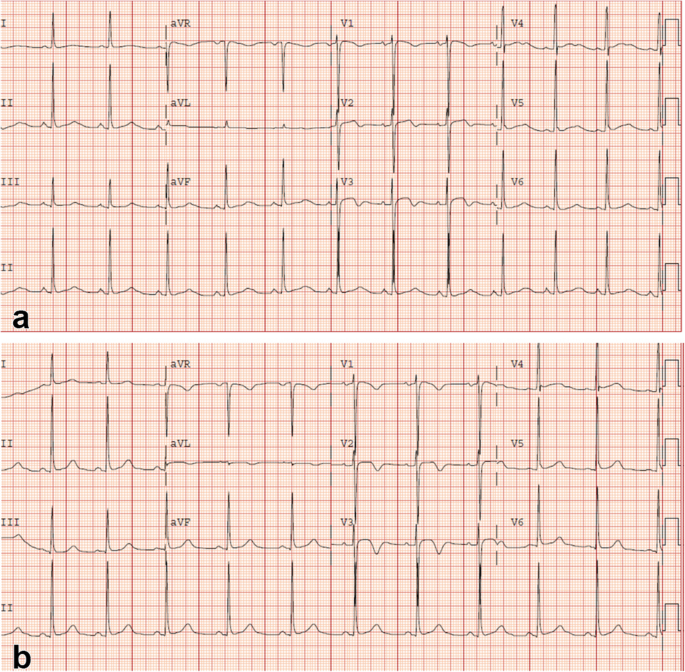

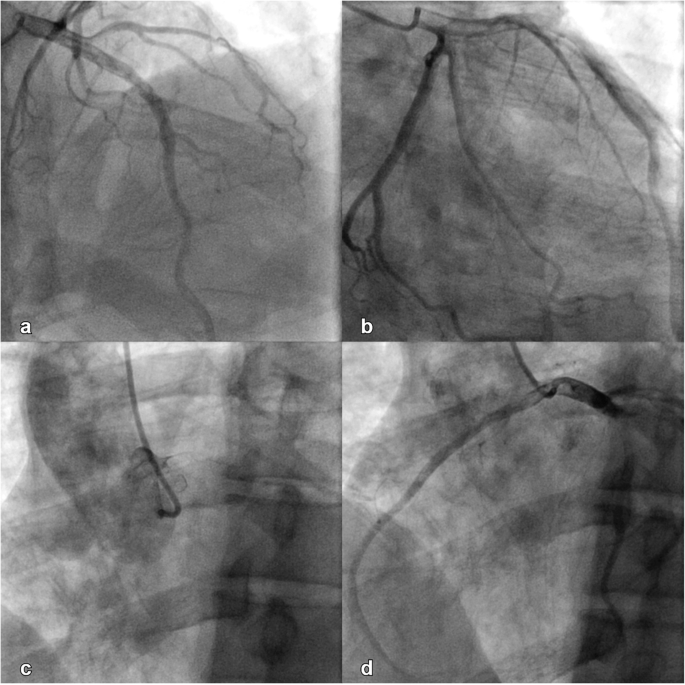

An initial ECG performed upon arrival at the ED showed 1-mm ST-segment elevations, T-wave inversions, and biphasic T-waves in his right precordial leads (Fig. 1a). He had persistent chest pain, and a repeat ECG 40 minutes after ED arrival showed persistent ST-segment elevations with dynamic T-wave changes, notably deep symmetric inversions in V1–V3 (Fig. 1b). Bedside transthoracic echocardiography showed normal left ventricular systolic function and no left ventricular hypertrophy or regional wall motion abnormalities. However, due to persistent chest pain and dynamic ECG changes concerning for critical stenosis high in the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery, consistent with Wellens syndrome, the patient underwent immediate invasive coronary angiography. Wellens syndrome is characterized by a typical pattern of the ST-T segment in leads V2 and V3, consisting of an isoelectric or minimally elevated (1-mm) takeoff of the ST segment from the QRS complex, a concave or straight ST segment passing into a negative T wave at an angle of 60 to 90 degrees, a symmetrically inverted T wave, and the absence of pathologic Q waves, in patients presenting with or without angina pectoris and minimal or no elevation of cardiac enzymes. Selective coronary angiography of our patient revealed angiographically normal coronary arteries but an anomalous origin of the dominant right coronary artery (RCA) from the opposite sinus (R-ACAOS) (Fig. 2a–d).

He was started on intravenous fluids and pain management for acute pancreatitis, given his elevated serum lipase and amylase levels (Table 1). His chest pain resolved within 24 hours of admission, accompanied by the resolution of his ECG changes with normokalemia. His epigastric pain subsided over the next 24–36 hours.

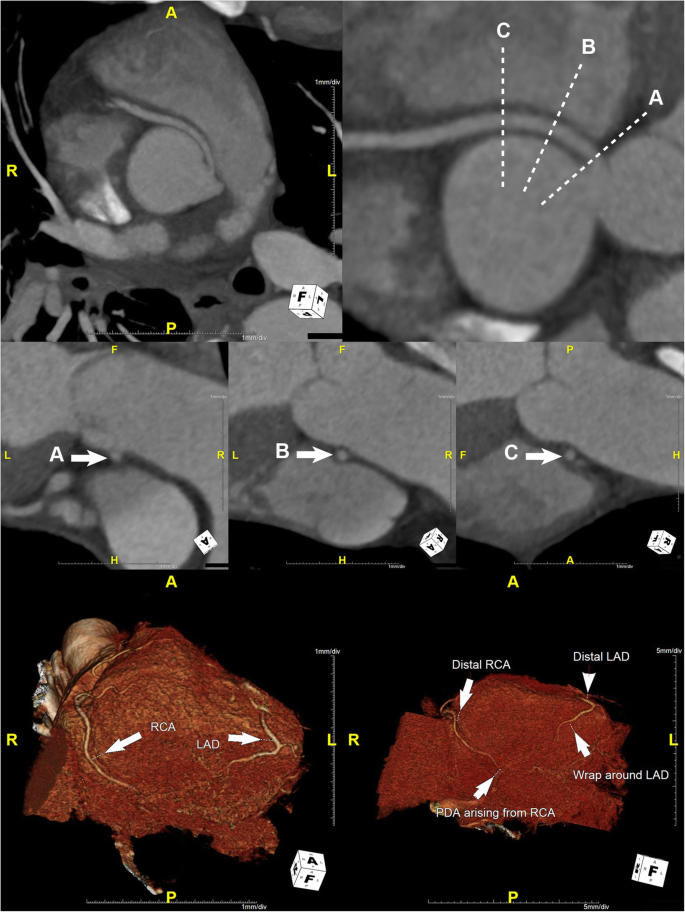

Computed tomography angiography (CTA) of the coronary circulation showed that the dominant R-ACAOS coursed between the aorta and the pulmonary trunk (Fig. 3) and demonstrated no evidence of coronary calcium or atherosclerotic changes. The patient underwent exercise testing with myocardial perfusion imaging prior to hospital discharge. He exercised for 10:04 minutes on a regular Bruce protocol (99% predicted maximal heart rate) with normal BP response and without ECG changes. Myocardial perfusion images showed no evidence of myocardial ischemia.

Disclaimer: This site is primarily intended for healthcare professionals. Any content/information on this website does not replace the advice of medical and/or health professionals and should not be construed as medical/diagnostic advice/endorsement or prescription. Use of this site is subject to our terms of use, privacy policy, advertisement policy. © 2020 Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt Ltd