- Home

- Editorial

- News

- Practice Guidelines

- Anesthesiology Guidelines

- Cancer Guidelines

- Cardiac Sciences Guidelines

- Critical Care Guidelines

- Dentistry Guidelines

- Dermatology Guidelines

- Diabetes and Endo Guidelines

- Diagnostics Guidelines

- ENT Guidelines

- Featured Practice Guidelines

- Gastroenterology Guidelines

- Geriatrics Guidelines

- Medicine Guidelines

- Nephrology Guidelines

- Neurosciences Guidelines

- Obs and Gynae Guidelines

- Ophthalmology Guidelines

- Orthopaedics Guidelines

- Paediatrics Guidelines

- Psychiatry Guidelines

- Pulmonology Guidelines

- Radiology Guidelines

- Surgery Guidelines

- Urology Guidelines

“Keyhole” Surgery Repairs Spina Bifida In Utero

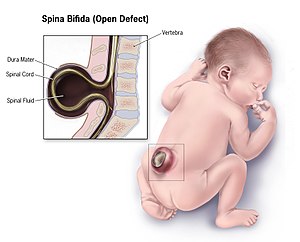

Surgeons at Huntington Hospital at Pasadena, have operated upon Spina bifida of a baby in Utero by keyhole surgery. Fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, is a delicate surgical procedure where fetal surgeons open the uterus and close the opening in the baby's back while they are still in the womb.

Gilda Giron was just 13 weeks pregnant when an ultrasound revealed her baby had myelomeningocele—the most severe form of open spina bifida, a birth defect that affects backbone development and can cause, among other things, debilitating neurological damage.

“This was a very emotional time for us,” says Giron, who already had two young children and was determined to protect her third. Surgeons could repair the defect in the womb, but she and her husband Arnuf wanted the safest option for both mother and child. While researching, they came across a promising new surgical method pioneered in Brazil and FDA-approved but performed only once thus far in the United States: in-utero percutaneous fetoscopic spina bifida repair. And as luck would have it, a team of doctors was piloting a clinical study at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, Children’s Hospital Los Angeles (CHLA) and Huntington Hospital on that very procedure, just miles from the Giron’s home.

On Feb. 19, Gilda became the first person in the western U.S. to undergo the most minimally invasive type of spina bifida repair currently available for a developing fetus. The surgery, which took place at Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, was a success, and three months later, at term and without need for a C-section, Gilda gave birth to Abigail, a healthy 5-pound 5-ounce baby girl.

“Both baby and mother are doing very well,” says Ramen Chmait, MD, who led this surgery and two others performed by the team. Several more are planned. “It is gratifying to see such a successful outcome as the result of the years we spent prepping for this moment.”

Chmait, the principal investigator for the Los Angeles site in the clinical study, is a CHLA Fetal-Maternal Center surgeon, an Associate Professor of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the Keck School and Director of Los Angeles Fetal Surgery. CHLA pediatric neurosurgeon Jason Chu, MD, MSc, and pediatrician Alexander Van Speybroeck, MD, Medical Director of CHLA’s Spina Bifida Program, both participated in the surgery and serve as co-investigators in the study. Other co-investigators include CHLA clinicians Philippe Friedlich, MD,MSEpi, MBA, Co-Director of the CHLA Fetal and Neonatal Institute, Mark Krieger, MD, CHLA Surgeon-in-Chief and Co-Director of the Neurological Institute, Eugenia Ho, MD, MPH, Director of the CHLA Fetal-Neonatal Neurology Program, Kathryn Smith, RN, MN, DrPH, and Douglas Vanderbilt, MD, MS, Director, Developmental-Behavioral Pediatrics Section at CHLA.

While spina bifida surgery in utero has been available for more than 10 years, this new method refines previous techniques by removing the need for large incisions altogether. Sometimes referred to as a “keyhole” surgery because it requires only small openings in the abdomen and uterus, percutaneous fetoscopic spina bifida repair has the potential to provide the similar benefit to the baby as compared to the standard open maternal fetal surgery approach, but with significant safety benefits to the mother, including:

- Reduced anesthesia needs

- Faster recovery time

- Less need for blood transfusion

- Opportunity for normal delivery, without the need for a C-section

- Reduced chance of complications in future pregnancies

To perform the procedure, the surgical team, which also included Huntington Hospital anesthesiologist Jae Elizabeth Townsend, MD, used precision tools and a camera to enter the abdomen and womb. The uterus was expanded with carbon dioxide to allow safe access to the fetus. They moved the exposed spinal cord back in place, patched the hole in the fetus’ spine, then sewed fetal skin over the patch. This not only protected underlying nerves and stopped the spinal fluid leakage, which untreated can cause lower body paralysis and disrupt the bladder and bowels, it also prevented amniotic fluid in the uterus from mixing with the fetal nervous system. In fact, a follow-up MRI showed Abigail’s hindbrain herniation—part of her brain that had dropped due to changes in fluid pressure—had reversed, the first indication the operation was a success.

“Abundant research shows that if you can repair spina bifida while the child is still developing in the womb, you are more likely to prevent significant developmental problems that can occur,” says Dr. Chu, who assisted with the neurological repair and is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Neurological Surgery at the Keck School. “We have to collect more data and perform more of these surgeries before we can say how successful this approach is, but early indications look very promising.”

Within a few hours of delivery, Abigail was transported to the Steven & Alexandra Cohen Foundation Newborn and Infant Critical Care Unit (NICCU) at CHLA for observation. Gilda was by her side a day later, and was able to nurse and bottle-feed Abigail in the NICCU, as Arnuf sat with them, smiling. After two weeks, Abigail went home.

“Typically, kids born with spina bifida spend more than two weeks in the hospital,” says Dr. Van Speybroeck, a Clinical Associate Professor of Pediatrics at the Keck School who has treated spina bifida patients for 15 years at CHLA and will monitor Abigail’s lifelong care. “We are going to share our information with all the doctors doing this to make sure we obtain the best outcomes for families. It has been a team approach the whole way and we want to keep it that way.”

“It takes a whole village to do this – specialists in the field of maternal, fetal and pediatric medicine,” explains Dr. Friedlich, a Professor of Clinical Pediatrics and Surgery at the Keck School. “It is life-changing and amazing; the NICCU staff loves to do this work.”

In light of the successful surgery and birth, Gilda says she’s staying optimistically cautious. “Abigail has done all the work – she is a little fighter,” she says, wiping a tear from her eye. “I work with special needs children as a full-time therapist and I wanted to do everything I could to make sure Abigail is healthy. But we are also realistic and know there is much that is unknown.”

Disclaimer: This site is primarily intended for healthcare professionals. Any content/information on this website does not replace the advice of medical and/or health professionals and should not be construed as medical/diagnostic advice/endorsement or prescription. Use of this site is subject to our terms of use, privacy policy, advertisement policy. © 2020 Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt Ltd