- Home

- Editorial

- News

- Practice Guidelines

- Anesthesiology Guidelines

- Cancer Guidelines

- Cardiac Sciences Guidelines

- Critical Care Guidelines

- Dentistry Guidelines

- Dermatology Guidelines

- Diabetes and Endo Guidelines

- Diagnostics Guidelines

- ENT Guidelines

- Featured Practice Guidelines

- Gastroenterology Guidelines

- Geriatrics Guidelines

- Medicine Guidelines

- Nephrology Guidelines

- Neurosciences Guidelines

- Obs and Gynae Guidelines

- Ophthalmology Guidelines

- Orthopaedics Guidelines

- Paediatrics Guidelines

- Psychiatry Guidelines

- Pulmonology Guidelines

- Radiology Guidelines

- Surgery Guidelines

- Urology Guidelines

Indian Perspective on Rational Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors, recommend experts

Experts have reviewed the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) guidelines and have presented an Indian Perspective and Recommendations on the Rational Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors which have appeared in Journal of Association of Physicians of India.

Acid peptic diseases (APDs) are prevalent worldwide; changing lifestyles and dietary habits may be attributable to the rising disease burden. A systematic review of 28 studies indicated ethnic and geographical variations in prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) [18.1–27.8 % in North America, 8.8–25.9 % in Europe, and 2.5–7.8 % in East Asia]. A survey of 1000 clinicians from India showed a high prevalence of GERD (39.2%), peptic ulcer disease (PUD, 37.1%) and non-ulcer dyspepsia (25.2%) with nearly 50% of patients requiring prompt endoscopy. Specific symptoms need to be identified accurately in order to avoid underdiagnosis or over-treating APDs.

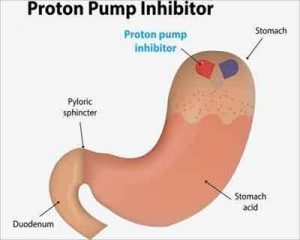

Medications available for treating these acid-related diseases are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RA), antacids, sucralfate and prostaglandin analogues. The PPIs available in the Indian market for clinical use are dexlansoprazole, dexrabeprazole, esomeprazole, ilaprazole, lansoprazole, omeprazole, pantoprazole, and rabeprazole. Their CDSCO (Central Drugs Standard Control Organization) approved indications are presented in Table 1.

Irrational prescription has been rampant with PPIs being prescribed to patients not presenting with valid indications warranting PPI use.5,6 A study by Churi et al. (2014) showed intravenous (IV) PPIs being inappropriately prescribed to 89.2% of internal medicine ward patients and 34.04% of surgery ward patients. Parenteral PPIs, being relatively expensive compared to oral PPIs and H2RAs, can significantly increase the cost for patients in hospitals. In another study at a tertiary care teaching hospital in Raichur, Karnataka, 50% of PPIs were orally prescribed to patients. Improper utilization of PPIs can lead to adverse effects, which in turn may result in an economic burden on patients seeking treatment. Quality variability across formulations manufactured by different companies may be an issue peculiar to India. In view of these concerns, the current expert recommendations have been developed to assist physicians in the rational use of PPIs.

Expert Panel Recommendations on Best Practices for PPIs Use in India

Best Practice Advice 1: Patients with GERD and acid-related complications (i.e., erosive esophagitis or peptic stricture) should take a PPI for minimum 12 weeks for healing of esophagitis and for maximum up to 48 weeks for symptom control.

Rationale: PPIs are highly effective in healing esophagitis and for GERD symptom control, and this benefit is likely to outweigh PPI-related risks. There is also good evidence that patients with acid-related complications such as peptic stricture are best treated with continued PPI.

Best Practice Advice 2: Patients with uncomplicated GERD including NERD who respond to short-term (less than 6 weeks) use of PPIs, should subsequently attempt to stop or reduce them. Patients who cannot reduce PPIs should be advised to undergo investigations to help distinguish GERD from a functional syndrome.

Rationale: Short-term PPIs are highly effective for uncomplicated GERD. Most patients with uncomplicated GERD respond to short-term PPIs and are subsequently able to reduce PPIs to less than daily dosing. Because patients who cannot reduce PPIs face lifelong therapy, we would consider testing for an acid-related disorder in this situation. Patients who do not respond to PPIs often do not have GERD.

Best Practice Advice 3: The patients with atypical symptoms of GERD such as non-cardiac chest pain may be given a 2-week trial of PPI. If they do not respond, they should be investigated to prove if they have GERD related chest pain.

Rationale: Most cases of non-cardiac chest pain may be related to reflux or esophageal motility disorder. A trial of PPI helps to differentiate.

Best Practice Advice 4: Patients with Barrett’s esophagus should take long-term PPI.

Rationale: PPIs have a clear symptomatic benefit and a possible benefit in slowing progression of Barrett’s. There is likely to be a net benefit for long-term PPIs in these patients

Best Practice Advice 5: Patients at high risk for ulcer-related bleeding from NSAIDs including aspirin should take a PPI if they continue to take NSAIDs

Rationale: PPIs are highly effective in preventing ulcer-related bleeding in appropriately selected patients who take NSAIDs including aspirin.

Best Practice Advice 6: The dose of long-term PPIs should be periodically re-evaluated so that the lowest effective PPI dose can be prescribed to manage the condition.

Rationale: Long-term PPI users often receive PPIs at doses higher than necessary to manage their condition. Since PPI reduction is often successful, it is logical to periodically reevaluate PPI dosing so that the minimum necessary dose is prescribed.

Best Practice Advice 7: Long-term PPI users should not use probiotics to prevent infection.

Rationale: There is no evidence for the use of probiotics to prevent infections in long-term users of PPIs.

Best Practice Advice 8: Long-term PPI users should not routinely raise their intake of calcium, vitamin B12 or magnesium beyond the Recommended Dietary Allowance (RDA).

Rationale: There is no evidence for or against use of vitamins or supplements beyond the RDA in long-term users of PPIs. If patients have proven or suspected nutritional deficiency then it is reasonable to supplement vitamins and minerals regardless of PPI use.

Best Practice Advice 9: Long-term PPI users should not be routinely screened or monitored for bone mineral density, magnesium, or vitamin B12. Low threshold for testing should be kept for those with any clinical features suspicious of or in presence of other risk factors for deficiency of magnesium or b12 or of osteoporosis.

Rationale: There is no evidence for or against dedicated testing for patients taking long-term PPIs. Such screening (e.g., for iron or vitamin B12 deficiency) is of no proven benefit.

Best Practice Advice 10: Patients on long-term PPI should not be routinely (yearly) monitored for serum creatinine unless there are other risks for renal monitoring.

Rationale: Based on the current literature, there is a small idiosyncratic risk of renal toxicity such as AIN with PPIs. Current data does not support routine monitoring for the vast majority of users.

Best Practice Advice 11: Specific PPI formulations should not be selected based on potential risks.

Rationale: There is no convincing evidence to rank PPI formulations by risk.

Best Practice Advice 13: Patients with dyspepsia who have predominant acid related symptoms (epigastric pain syndrome) should receive short-term PPI.

Rationale: There is likely to be a net benefit for short-term PPIs in these patients.

For more details click on the link: www.japi.org

Disclaimer: This site is primarily intended for healthcare professionals. Any content/information on this website does not replace the advice of medical and/or health professionals and should not be construed as medical/diagnostic advice/endorsement or prescription. Use of this site is subject to our terms of use, privacy policy, advertisement policy. © 2020 Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt Ltd