- Home

- Editorial

- News

- Practice Guidelines

- Anesthesiology Guidelines

- Cancer Guidelines

- Cardiac Sciences Guidelines

- Critical Care Guidelines

- Dentistry Guidelines

- Dermatology Guidelines

- Diabetes and Endo Guidelines

- Diagnostics Guidelines

- ENT Guidelines

- Featured Practice Guidelines

- Gastroenterology Guidelines

- Geriatrics Guidelines

- Medicine Guidelines

- Nephrology Guidelines

- Neurosciences Guidelines

- Obs and Gynae Guidelines

- Ophthalmology Guidelines

- Orthopaedics Guidelines

- Paediatrics Guidelines

- Psychiatry Guidelines

- Pulmonology Guidelines

- Radiology Guidelines

- Surgery Guidelines

- Urology Guidelines

BAD Guidelines for the management of onychomycosis

British Association of Dermatologists have released its Guidelines for the management of onychomycosis.They have been published in British Journal of Dermatology.Onychomycosis is among the most common nail disorders in adults. The management of onychomycosis requires the correct mycological identification where possible, assessing disease susceptibility and risk factors and deciding what therapy options are most suitable for the clinical form of onychomycosis and aetiological agent.

Definition of onychomycosis

- The term tinea unguium is used to describe dermatophyte infections of the fingernails or toenails. Onychomycosis is a less specific term used to describe fungal disease of the nails. The condition is worldwide in distribution. In addition to dermatophytes, it can be caused by a number of other moulds and by Candida species

Aetiology

- Risk factors for onychomycosis include:

- increasing age

- peripheral vascular disease

- trauma and hyperhidrosis

- Fungal nail disease is more prevalent in:

- men

- individuals with other nail problems such as psoriasis

- people with immunosuppressive conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or HIV infection

- those taking immunosuppressive medications

Rationale for treating onychomycosis

- Onychomycosis can have a significant impact on the quality of life of patients. Problems associated with onychomycosis include discomfort, difficulty in wearing footwear and walking, cosmetic embarrassment and lowered self-esteem

Classification/clinical manifestations

- Onychomycosis is a fungal infection caused by various pathogens, which can adopt any of several clinical patterns. The five main clinical patterns are:

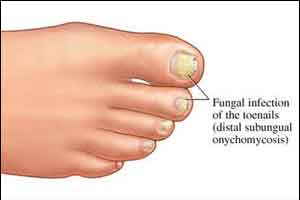

Distal and lateral subungual onychomycosis (DLSO)

- Most common presentation of dermatophyte nail infection. Toenails are more commonly affected than fingernails. The fungus invades the nail and nail bed by penetrating the distal or lateral margins. The affected nail becomes thickened and discoloured, with a varying degree of onycholysis (separation of the nail plate from the nail bed), although the nail plate is not initially affected. The infection may be confined to one side of the nail or spread to involve the whole of the nail bed. In time the nail plate becomes friable and may break up

- The most common causative organism is T. rubrum. As DLSO has a similar clinical presentation whether caused by dermatophytes or nondermatophytes, it is important to obtain a nail sample for mycological examination so that the causative organism can be identified

Superficial white onychomycosis

- Infection usually begins at the superficial layer of the nail plate and spreads to the deeper layers. Crumbling white lesions appear on the nail surface, particularly the toenails. These gradually spread until the entire nail plate is involved

Proximal subungual onychomycosis

- Least common presentation of dermatophyte nail infection in the general population, it is common in people with AIDS. Infection often spreads rapidly from the proximal margin and upper surface of the nail to produce gross white discoloration of the plate without obvious thickening

Endonyx onychomycosis

- Instead of invading the nail bed through the nail plate margin, the fungus immediately penetrates the nail plate keratin. The nail plate is discoloured white in the absence of onycholysis and subungual hyperkeratosis. The most common causative organisms are T. soudanense and T. violaceum

Total dystrophic onychomycosis (TDO)

- Any of the above varieties of onychomycosis may eventually progress to TDO, where the nail plate is almost completely destroyed. Primary TDO is rare and is usually caused by Candidaspecies, typically affecting immunocompromised patients

Diagnosis

- The clinical signs of tinea unguium are often difficult to distinguish from those of a number of other infectious causes of nail damage, such as Candida, mould or bacterial infection. Unlike dermatophytosis, candidosis of the nails usually begins in the proximal nail plate, and nail fold infection (paronychia) is also present. Bacterial infection, particularly when due to Pseudomonas aeruginosa, tends to result in green or black discoloration of the nails. Sometimes bacterial infection can coexist with fungal infection and may require treatment in its own right

- Other less common dystrophic nail conditions mimicking onychomycosis are Darier disease and lichen planus, and ichthyotic conditions such as keratosis, ichthyosis and deafness syndrome. Often yellow nail syndrome is falsely identified as a fungal infection. Light green-yellowish pigmentation of the nail plate, hardness and elevated longitudinal curvature are the key clinical characteristics of this nail disease

- Repetitive trauma to the nail plate can also result in the abnormal appearance of nails. The nail bed will appear normal if the symptoms are caused by trauma rather than onychomycosis, with a characteristic pattern of intact longitudinal epidermal ridges stretching to the lunula

Essential investigations and their interpretation

- The clinical characteristics of dystrophic nails must alert the clinician to the possibility of onychomycosis. Laboratory confirmation of a clinical diagnosis of tinea unguium should be obtained before starting treatment. This is important for several reasons: to eliminate non-fungal dermatological conditions from the diagnosis; to detect mixed infections; and to diagnose patients with less responsive forms of onychomycosis, such as toenail infections due to T. rubrum. Good nail specimens are difficult to obtain but are crucial for maximising laboratory diagnosis

- Material should be taken from any discoloured, dystrophic or brittle parts of the nail. The affected nail should be cut as far back as possible through the entire thickness and should include any crumbly material. Nail drills, scalpels and nail elevators may be helpful but must be sterilised between patients. When there is superficial involvement (as in SWO) nail scrapings may be taken with a curette. If associated skin lesions are present, samples from these are likely to be infected with the same organism, and are more likely to give a positive culture.

- Traditionally, laboratory detection and identification of dermatophytes consists of culture and microscopy, which yields results within approximately 2–6 weeks

Treatments

- Asymptomatic onychomycosis (especially in elderly people) may not require drug therapy

- Tables 1 and 2 summarise the drug therapies recommended in this guideline. Please see the full guideline at for full details of the evidence www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=2125&itemtype=document

Summary of drug therapies in adults

Systemics | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Topicals | |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Other topical treatments

- Once-daily application of topical 10% efinaconazole, a new triazole antifungal agent, has recently been found to be more effective than vehicle in the treatment of onychomycosis, with mycological cure rates approaching 50% and complete cure (defined as mycological and clinical cure) in 15% of patients after 48 weeks of application

- New topical formulations of terbinafine are being investigated, with early data showing promising clinical and mycological results

- Butenafine, bifonazole, salicylic acid, over-the-counter mentholated ointment, ozonized sunflower oil, and undecenoates have been used, but there are limited data to support their use as monotherapy for onychomycosis

- A 40% urea ointment is now available

Summary of drug therapies in children (age 1–12 years)

Treatment in children | Suggested method of use and monitoring |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Treatment failure or relapse?

- Onychomycosis has often been associated with high recurrence rates (40–70%), and many patients have a long history of disease recurrence. The term ‘recurrence’ suggests both relapse and reinfection. In treatment relapse, infection is not completely cured and returns. This implies treatment failure

- Fungal-free nails are the goal of antifungal therapy in onychomycosis. Because of the slow growth pattern of the toenails, up to 18 months is required for the nail plate to grow out fully. Therapeutic success of antifungal therapy of onychomycosis depends on the newly grown-out nail plate being fungus free

- The major risk factors for recurrence include family history, coexisting ancillary clinical conditions (diabetes, arterial and vascular diseases, Down syndrome, Raynaud syndrome), immune suppression and acquired or inherent immunodeficiency. Other previously implicated prognostic factors are coexisting bacterial/viral nail infections, erroneous diagnosis, poor compliance, antifungal resistance and poor choice of antifungal therapy. Furthermore, the role of disease-causing fungi is also critical. Generally, onychomycosis caused by nondermatophytic moulds does not respond to oral antifungal therapy, and current effective management options are limited

Prevention

- Strategies include:

- wearing protective footwear to avoid re-exposure

- application of an absorbent powder, and antifungal powders in shoes and on the feet

- wearing cotton, absorbent socks

- discarding all ‘old and mouldy’ footwear

- keeping nails as short as possible and to avoid sharing toenail clippers with family members and friends

- treating all infected family members at the same time to avoid reinfection

- wearing comfortable, well-fitting shoes and to avoid trauma to the nail

- advise patient (if relevant) to be aware of the risk of infection in nail salons—visit salons that employ a sterile technique

Summary of the management of onychomycosis

- Onychomycosis is among the most common nail disorders in adults. The management of onychomycosis requires the correct mycological identification where possible, assessing disease susceptibility and risk factors and deciding what therapy options are most suitable for the clinical form of onychomycosis and aetiological agent. Some patients will require monitoring, particularly high-risk patients, and at the end of the recommended course of treatment they should be reassessed for mycological cure (which is defined as negative mycological analysis and a normal nail)

Criteria for referral

- Refer to dermatology when:

- oral antifungal treatment is required for a child under 18 years

- diagnosis is uncertain

- treatment is unsuccessful

- person is immunocompromised

- Refer to podiatry if nails are traumatised by the person’s footwear, or deformed toenails traumatise adjacent toes

Please see full guideline for further information on:

- Candidal onychomycosis

- Mould (nondermatophytic) infection of nails

- Nondermatophyte moulds

- Molecular diagnostics

- Histology

- Treatment of paediatric onychomycosis

- Combination treatment

- Onychomycosis in special groups

- Surgery, lights, and lasers

For further reference log on to :

www.bad.org.uk/shared/get-file.ashx?id=2125&itemtype=document

British Association of DermatologistsBritish Journal of DermatologyCandidadermatophytesDiabetes Mellitusfungal infectionHIV infectionhyperhidrosismycologicalonychomycosisperipheral vascular diseasePseudomonas aeruginosatoenailsTotal dystrophic onychomycosis

Next Story

NO DATA FOUND

Disclaimer: This site is primarily intended for healthcare professionals. Any content/information on this website does not replace the advice of medical and/or health professionals and should not be construed as medical/diagnostic advice/endorsement or prescription. Use of this site is subject to our terms of use, privacy policy, advertisement policy. © 2020 Minerva Medical Treatment Pvt Ltd